In the grim milieu of Japan’s post-economic bubble era, a surge of horror films released shaped their narratives around prevailing issues related to family, specifically between parent and child. Aside from Ring (1998), Nakata Hideo Dark Water (2002) is exemplarily here in that symbolic violence recalls itself through disrupting semiotics associated with water. Water as vital source of life signifies death. Motherhood is also symbolized similarly, acting as an inhibiting force toward female independence. This essay shall argue how maternity in Dark Water aligns with traditional values and that the protagonist’s acceptance of her role was an attempt at solving decaying family structures in Japan. An overview of the post-bubble era will describe how such issues arose. Later, water’s symbolism culturally specific to Japan will be discussed, tying it with the film’s supernatural events.

To begin, Japan’s post economic bubble period after 1995 was marked by soaring debt, tax hikes and devastating class division that left the country in deep recession (Preyde, 2019: 34, 37, 40). Amidst the horrors of the Tokyo subway sarin attack, the Great Hanshin Earthquake, and the “otaku” child killer, reactionary widespread consumerism took momentum.

As newer technologies were rapidly introduced, there began a “solitary absorption of electronic media, particularly electronic games or the Internet,” (Taylor, 2006: 168). With a grim reality surrounding them, Japanese people (particularly youth) sought out the fictional worlds digital media presented them. Yet, what of the older generation still bound by traditional values? How could parents adjust to a lost decade where promises of peace and stability were betrayed?

Despite Japan’s drive for liberalism, gender roles during the era became far more exacerbated than before. The economic climate promoted more dependence on a working husband. Women’s responsibilities over full-time child-rearing became burdensome (Sugimoto, 2010: 160, 171). Housewives’ isolated lifestyle in metropolitan areas neglected by her husband combined with the turbulent, violent events conspiring daily caused a great deal of stress. Sugimoto notes that women then suffered from a “mother-pathogenic disease’” where her anxieties lead to neurotic behaviour which damaged the child’s mental health (2010: 184).

For instance, mothers become over-protective, obsessing over the child’s school marks with them experiencing psychosomatic symptoms (stomach-aches), social anxiety (school phobia) or even autism as a result. Despite the father acting as the main income provider, his absence from home contributed to his dependents’ distress.

The husband’s neglect of over child-rearing stemmed from a highly demanding lifetime employment system (Preyde, 2019: 44). Long work hours combined with a competitive salary where the threat of entrenchment loomed over his shoulders pressured the father to spend more time at work, in hopes of a promotion to a position with welfare benefits. Nevertheless, the salaryman’s job security was constantly at threat, his dedication to working over the family worsened household, with mother and child reaping the consequences.

An eternal bond between them was present throughout history. Traditional gender roles defined women as primary caregivers, tying them to the household through religious obligation. Buddhism in Medieval Japan spread the belief that mother and child were conjoined entities, losing ownership over the child after they had grown.

Women thus functioned as corporate value for noble families (Glassman, 2008). In other words, they were transactions. Childbirth then was life-threatening because the soon-to-be heir was a foetus in the womb. If women who aborted or killed the child, or they had died during pregnancy, society saw them as impure.

Water’s link with motherhood became a violent tool that socially and biologically ostracized females who lost their child during birth. “The salvation offered women within the Sino-Buddhist cult of ancestors is salvation as mothers—that is, salvation by virtue of the very biological potential that would come to spell their doom,” (Glassman 2008: 177). Since female bodies were viewed as vessels, women who failed bearing children were sinners. Glassman notes that women who miscarried or aborted children in 16th century Japan were condemned to drowning in an underworld filled with lakes of menstrual blood (Glassman 2008).

Additionally, The Ketsubonkyō (Blood-bowl Sutra) proposed liberation from hell was possible. After struggling to find his mother in tenkai (heaven) Buddha’s disciple Mokuren used his supernatural powers to descend into hell and rescue her. Suffering from eternal hunger with every attempt at feeding her futile, Mokuren turns to Buddha for advice. His advice is a festive celebration of food-offering now known as Obon ( Nichiren Shu Portal, n.d.). Nonetheless, Ketsubonkyō corrupts women and water for the sake of patriarchal beliefs.

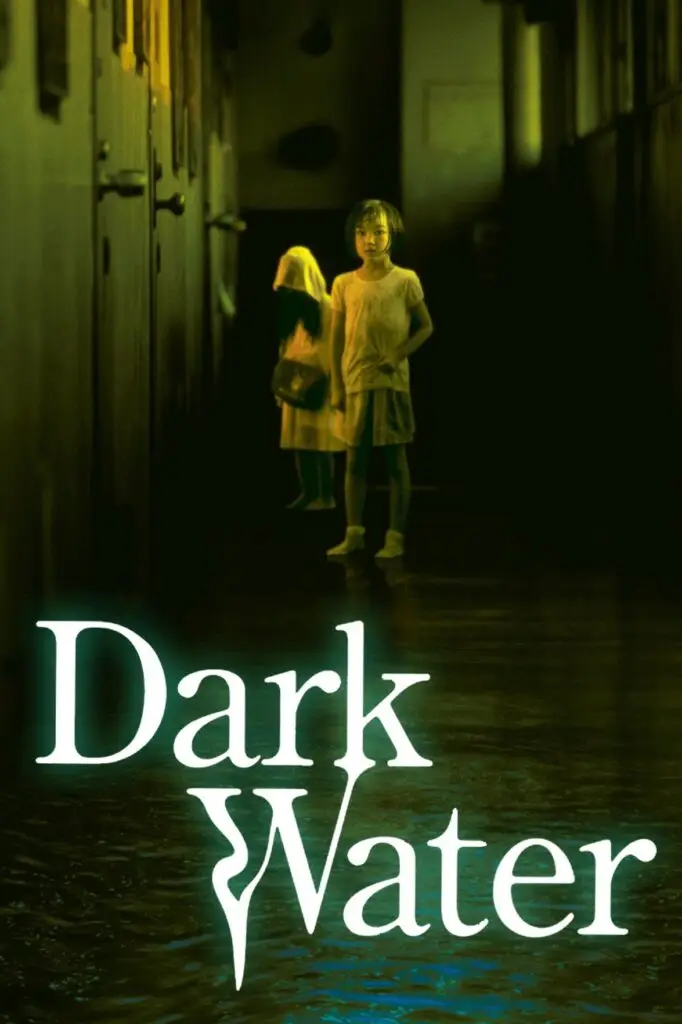

Water in Japanese horror cinema is associated with chaos and impurity (Balmain, 2008: 171). In Dark Water, shots of mould, rust, heavy rain, and flooding overwhelm recently divorced Yoshimi and her daughter Itsuko who have just moved in. To figure out the source of these strange occurrences happening around them, Yoshimi ventures upstairs, discovering that leak damaging her home is not on account of harsh weather but by a malevolent spirit.

Davisson explains that yūrei are“spirits of the departed – both symbols of the past reaching a cold, dead, and often unwelcomed hand into the comfortable present,” (2015: 11). Yūrei disrupt everyday reality, often to the point where their last painful moments on earth playout. Mitsuko, who previously inhibited the unit a floor up from Yoshimi’s, was left unsupervised by her mother, spending time up on the rooftop. Her red bag fell into the water tower while playing, she reached in trying to retrieve it but drown as a result. Water therefore represents failed maternal responsibility over a child similarly to the Ketsubonkyō.

Additionally, Mitsuko targets Yoshimi precisely because Yoshimi has left Itsuko unsupervised. Mitsuko befriends Itsuko whose closely resemble each other, from being socially isolated at school, fatherless to spending little time with their working mothers. Mitsuko later causes the various plumbing issues in the apartment, draws Ikuko toward the water tower she had drowned in, all to torment Yoshimi’s poor mothering.

Until Yoshimi assumes better responsibility, Mitsuko will not cease disturbing them. According to Foster, yūrei arebound to the location where they had died (Foster 2015). However unwilling victims may be, the ghost can only disappear once their unfulfilled wish is granted. Yoshimi’s hauntings gradually escalate from poor building maintenance to natural disaster. Since Yoshimi ignored her obligations for Itsuko just like her mother did, Mitsuko haunts Yoshimi. However, why did Yoshimi not move away? As the film reveals, she remains because she is immensely sympathetic toward Mitsuko.

While a flood surges down the corridors, Yoshimi does not head for her daughter but instead runs straight toward Mitsuko. Interpreting this as martyrdom is too simple. In various parts of the film, Mitsuko’s flashbacks are intercut with Ikuko’s scenes, who – referring to how these sequences are edited – Yoshimi both neglects. The mother’s investigations into Mitsuko’s death prompted her guilt for abandoning Itsuko. She therefore fulfils her motherly duties through death, joining Mitsuko in the afterlife.

To close, Dark Water uses water as a symbol of maternal responsibility. Neglect of the child arises from the absent father and struggling single mother isolated in the backdrop of a rapidly urbanizing society caught in the grips of socio-economic despair. Women are an active part of the workforce however, their traditional roles over child-rearing, along with how a firmly embedded patriarchal structures are in society places them in a constant tug-of-war between personal/parental obligation. In the past, failing to meet these duties was a sin.

Considering Japan’s post-bubble context where males over-dedicated themselves to their profession, women receive the most punishment compared to men. Dark Water portrays a self-reliant professional woman acknowledging her role as a primary caregiver through unconditional maternal love. Unlike the father who is unbound by familial obligations, the mother’s freedom is sacrificed in the sake of mothering. This grim reality is signified through contaminated water that slowly floods into the female mind, drowning them in the depths of subjugation.

References

- Balmain, C. (2008). Introduction to Japanese horror film. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press. pp.171

- Carroll-Preyde, M. (2019). Crisis and transformation in Hesei Japan. [pdf] pp.37–44. Available at: https://yorkspace.library.yorku.ca/xmlui/bitstream/handle/10315/37440/Carroll-Preyde_Myles_R_2019_PhD.pdf [Accessed 3 Aug. 2023].

- Dark Water [Motion Picture]. (2002). Japan: Office Augusta Co. Ltd.

- Davisson, Z. (2015). Yūrei: the Japanese ghost. Seattle, Wa Chin Music Press. pp. 11

- Foster, M.D. (2015). The book of yōkai: mysterious creatures of Japanese folklore. pp. 23. Oakland, California: University Of California Press.

- Nichiren Shu Portal (n.d.). Obon and segaki. Available at: https://www.nichiren.or.jp/english/buddhism/obon_segaki/page02.php [Accessed: 27 June 2025].

- Stone, J.I., Walter, M.N., 2008. Death and the afterlife in Japanese buddhism. University of Hawai’i press, Honolulu (T.H.), pp. 176-180.

- Sugimoto, Y. (2010). An Introduction to Japanese Society. pp. 160, 184. Cambridge University Press.