Anime remains the most popular content on streaming platforms worldwide. Valued at US$24 billion,1 anime makes up 45% of content viewed on premium video-on-demand services, with Japanese live-action only being 22%. 2 Audiences rarely view Japanese television shows, with niche titles such as Hibana: Spark (2016)and Alice in Borderland (2020) gaining attention. Older programs by local stations that differ vastly in quality are often neglected. This article argues that romantic dramas represent Japan better than anime by examining how its depiction of love as a thrilling, “magical” experience appealed to young audiences’ desires successfully through various production design choices and genre conventions throughout their brief history.

Romance dramas emerged in two phases during the late 80s and early 90s. “Trendy” dramas that appeared in 1985 highlighted popular lifestyles of the bubble economy. Viewership declined due to mismatched preferences between producers and audiences. Kitazawa (2012) explains that youth’s interest for jidaigeki and Japanese history was poor, resulting in a generational gap between them and aging viewers who grow up fond of these heavily masculine genres. 3 Women in their 20s were eventually identified as a potential target audience that could increase ratings.

Unfortunately, they discovered that instead of watching television, women spent their time in restaurants, bars, cafes, and hotels. Stations and sponsors later co-operated in creating love stories featuring lavish apartments, designer fashion, sports cars, all set in Tokyo. Furthermore, theme songs sung by iconic musicians of the time were part of a strategy to capture the hearts of these women, who often starred in lead roles.

Trendy dramas placed more emphasis on character relationships, dialogue and performance with plots tending to be relatively straight forward, creating a light-hearted, artificial microcosm that avoided depicting troublesome familial and social dynamics. 4 In other words, trendy dramas avoided portraying the difficulties of love faithfully, placing less importance on realism than on romantic thrills.

To illustrate, stories always had love triangles between a beautiful main heroine, an attractive supporting character, and a simple-minded hero who held affluent jobs in entertainment, news, arts, or sales. Suspense arose from who the hero would choose in the end. Heroines were either a friend, colleague, or past lover, who both try to get the male lead. The male support also stirs trouble; a womanizer who may get either heroine but eventually cheats on them with someone else. Depending on the show’s overall ratings across its three-month broadcast over a designated time slot varying per station (e.g. Monday 9PM for Fuji TV), the story could conclude with the hero marrying the heroine or sub-heroine.

Another part of the “magic” were dramatic moments such as confessions, kisses, or breakups that utilized pop music to “magnify characters’ feelings and encourage identification.” 5

Idols in these scenes elevated the commercial viability for promotional campaigns. Sponsors also wanted more brand recognition. Costumes, makeup, and sets were stylish, glamorous, and overly decorative, paired with vibrant lighting and lush colours. Coupled with extreme wide shots of Tokyo’s various sightseeing spots and closeups of gorgeous stars, trendy dramas were no different from advertisements.

Ultimately, these shows were successful only in an economically prosperous era. The bubble was soon to burst, and audiences grew tired of these highly consumerist depictions of modern life that they found superficial.

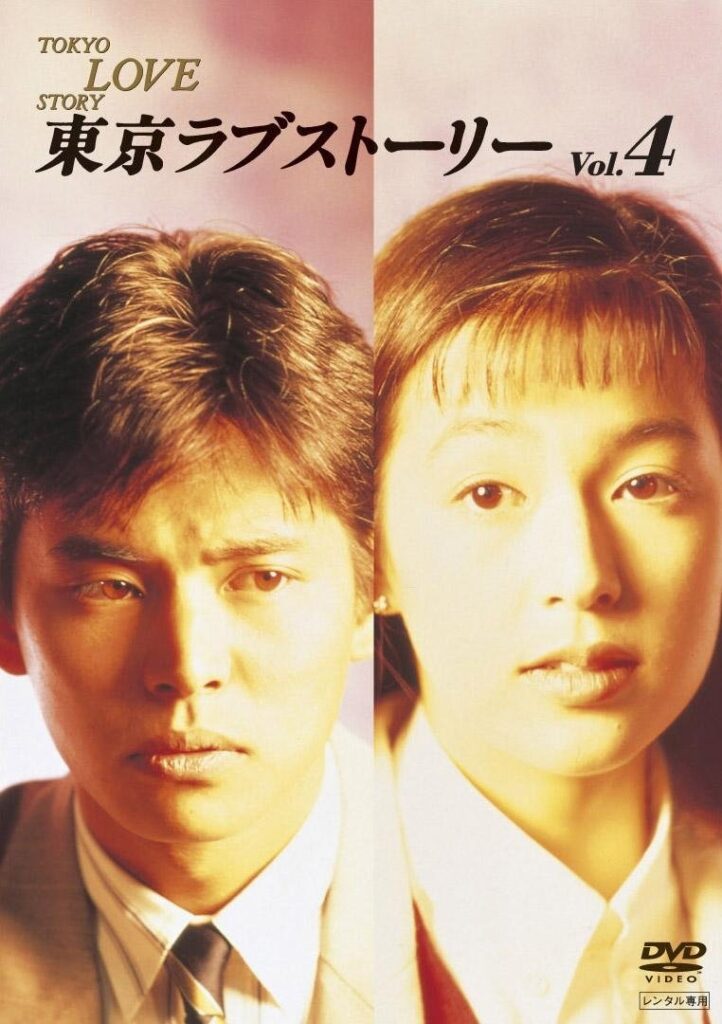

In response, producers and writers turned their efforts toward genuine characters and a more realistic depiction of Tokyo. As Former Fuji TV producer Ōta Tōru (2010) states, “our strategy was to drive the audience to be deeply involved in the romance by making it look realistic and unattainable.” 6 After he released Tokyo Love Story (1991), thepure love boom began.

Again, the attractive features trendy dramas had were kept but held less importance than the gradual development of the cast as they navigate complex relationships. Ōta aimed to “really make the audience sympathize with the character and weep for her,” abandoning happy endings for tragic ones because “the surprising fact is that a lot of the female viewers are living unhappily in real life. Somehow the viewers would feel disappointed when the drama heroine wins her love.” 7 The hero and heroine inpure love dramas rarely got together — a trip abroad, a marriage with another character, sickness or death separates them forever.

“Magic” here is a painful, moving experience that speaks volumes about the various intricacies associated with falling in love. Tokyo Love Story’s writer Sakamoto Yuuji exemplifies this, while Kitagawa Eriko rather “privileges falling-in-love as… uncompromising, vital, and liberating.” 8 For female viewers, love is a transformative process of self-affirmation. Other noteworthy writers include Nojima Shinji and Okada Yoshikazu who all stylistically humanized characters on-screen through deeper explorations of romance.

Unfortunately, pure love dramas could not persist any longer. Yamato Nadeshiko (2000) was marketed as the last trendy drama of the century years after the economic bubble burst. Broadcaster later had a newfound interest in darker, plot-heavy mysteries. The “magic” wore off.

Nevertheless, romance dramas successfully appealed to younger female viewers with various storytelling devices, production choices and casting decisions. Love stories in the city where characters led glamorous lifestyles were at the forefront, but audiences found it too shallow. Pure love dramas arrived, which depicted romance earnestly, making viewers sympathize and identify with characters. These stories became sensations not just in Japan, but also in Taiwan, Singapore, Malaysia, South Korea, and Hong Kong. 9 Fortunately, romance dramas are now accessible outside of Asia. Although limited, popular romance dramas on Netflix are available in multiple languages as per a deal with Fuji TV. 10

Hopefully, this article encourages Japanese learners to turn away from anime momentarily, exposing themselves to a vital part of Japan’s creative economy. Moreover, dramas depict broader socio-cultural aspects of Japanese life in a way animation cannot readily portray. Lastly, romantic dramas prove that love is a universal language that transcends national borders, understood by us all.

Pure Love Dramas available on Netflix:

- Tokyo Love Story (1991)

- The 101st Proposal (1991)

- Beach Boys (1997)

- Beautiful Life (2000)

- Yamato Nadeshiko (2000)

References:

- Petit, A., Steinberg, M., Crawford, C., Ristola, J., Altheman, E., Ciarma, S., Berndt, V., 2022. Anime Streaming Platform Wars: A Platform Lab Report, pp.1, 15. https://doi.org/10.13140/RG.2.2.34667.67368

- Online Media Report: Japan Online Video Consumer Insights & Analytics, 2022. Media Partners Asia, pp. 1. Available at: https://media-partners-asia.com/AMPD/Q4_2022/Japan/PR.pdf [Accessed on: 5/7/2025]

- 北澤由美子, 2012. 時代で読み解くドラマの法則. 早稲田社会科学総合研究. 別冊, 2011年度学生論文集 161.

- Ito, M. ‘The Representation of Femininity in Japanese Television Dramas of the 1990s’, inIwabuchi, K. (Ed.), 2010. Feeling Asian modernities: transnational consumption of Japanese TV dramas. Hong Kong University Press, Hong Kong, pp. 37.

- Tsai, E. ‘Empowering Love: The Intertextual Author of Ren’ai Dorama’, inIwabuchi, K. (Ed.), 2010. Feeling Asian modernities: transnational consumption of Japanese TV dramas. Hong Kong University Press, Hong Kong, pp. 58.

- Ōta, T. ‘Producing (Post-)Trendy Japanese TV Dramas’, in Iwabuchi, K. (Ed.), 2010. Feeling Asian modernities: transnational consumption of Japanese TV dramas. Hong Kong University Press, Hong Kong, pp. 77.

- Ōta, 2010: 83, 74.

- Tsai, 2010: 54.

- Wong, L., 2023. “Reminiscing” the popularity of Japanese television dramas outside Japan. https://doi.org/10.15200/winn.148854.46042

- Reign, 2024. Fuji TV is Coming To Netflix: Here Are 9 Shows To Add To Your Watchlist. Trill. Available at: https://www.trillmag.com/entertainment/tv-film/fuji-tv-is-coming-to-netflix-9-shows-to-add-to-your-watchlist/ [Accessed on: 21/5/2025].

About Me:

Holding a Bachelor of Arts in Motion Picture, film, television, mass media & popular culture are at the forefront of my Japanese studies. From books, manga, anime, drama and cinema, my hobbies are all centred on improving my language abilities and cultural knowledge. I currently research Japanese television in preparation for the MEXT scholarship.