Have you ever visited a Shinto shrine in Japan? If not, this article will make you feel as if you just did!

I distinctly remember one of the first shrines I visited in Japan. South of Tokyo, in an area known as Kamakura, lies Tsurugaoka Hachimangu. Those who have visited Kamakura may know it for the beaches and the famous Buddha, sites I did indeed see (I fondly remember wandering around the Buddha in awe). I was visiting a friend who was studying in Tokyo, and as it was my first time in Japan, I was keen to see the sights and experience the country. The shrine grounds were large, with a long walkway leading up to the main area, gardens and smaller shrines flanking on each side. The architecture and the atmosphere fascinated me, and we explored the area for what seemed like hours. Little did I know that that would be a catalyst for my interest in shrines and religion, leading to a multi-year global adventure, from Seattle, to Tokyo, to London.

Shinto is one of the main religions in Japan. Its definition has been up for heavy debate, some call it ‘indigenous’, while others say that you can’t even call it a religion. In essence, Shinto is an animistic belief that there are deities, or ‘kami’, residing in the natural world, from the trees, to the rocks and the sea, and their relationship with people. Shrine grounds are sacred spaces and the enshrined deity varies from shrine to shrine. At Tsurugaoka Hachimangu, the deity is Hachiman, the god of war and warriors; at Fushimi Inari shrines, known for their long rows of torii gates, the deity is Inari, the god of agriculture, industry, and other practices.

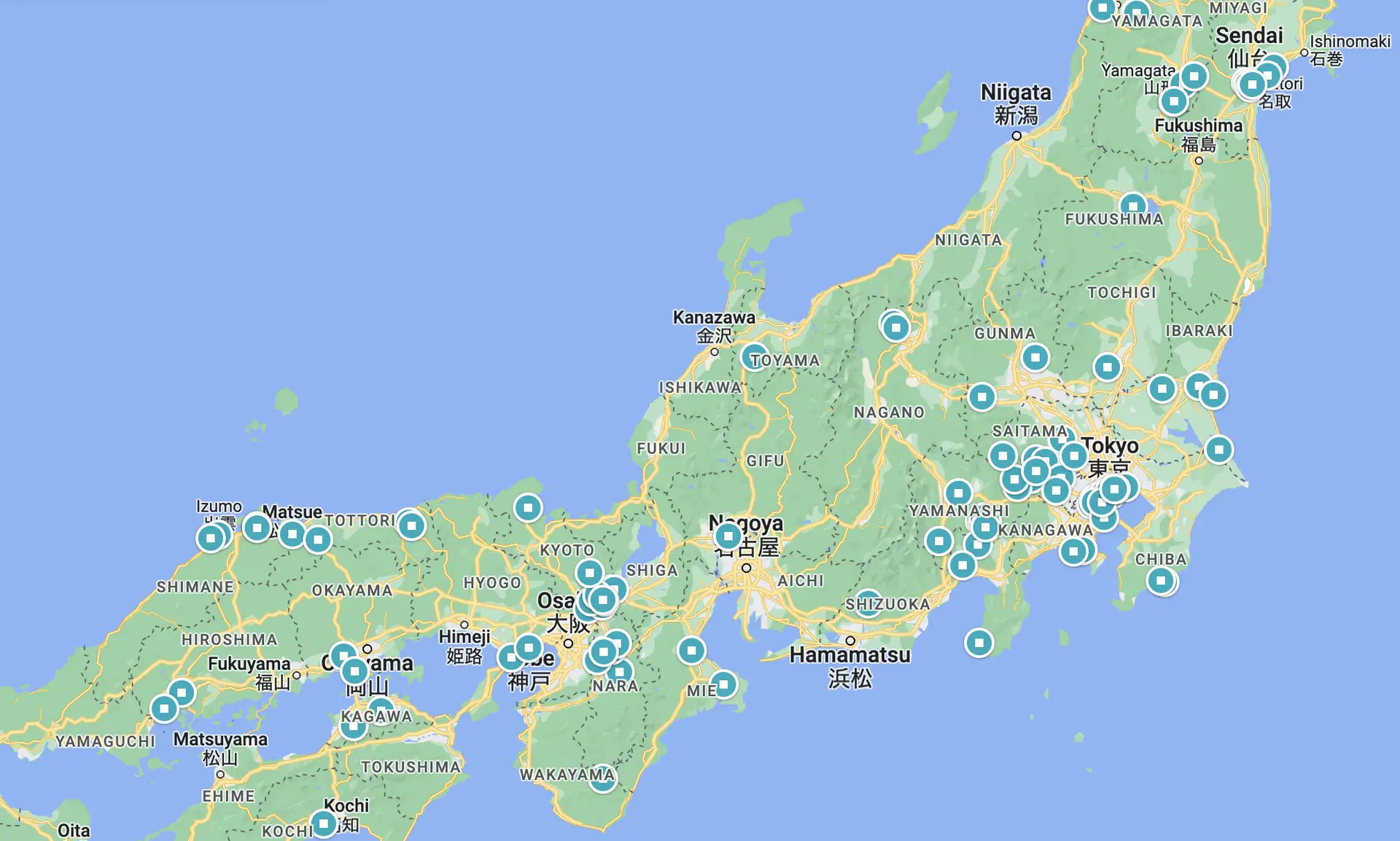

Shinto Shrines are eponymous with Japan. With their distinct red (but not always!) torii gates and architecture, they stand out from the cityscape and the skyscrapers that dominate Japan’s cities. There are nearly 80,000 shrines within the country, all unique in their own right. From a shrine dedicated to the weather to one for passing your school exams, if you want luck or good faith towards any pursuit, there will be a shrine for it.

As you approach a shrine you’ll notice the large torii gate first. It signifies that you are stepping into sacred ground, the ground of the kami. Tradition states that you bow before the gate and make sure to walk on either the right or the left side of it, as the centre is reserved for the kami!

As you walk the main grounds, or ‘keidai’, you’ll see statues of guard dogs known as ‘komainu’, lanterns, and other decorations around the area. You’ll notice large ropes tied around trees, and other objects, these are known as ‘shimenawa’, and are used as wards against evil and signifiers of a kami in dwelling. Shrines are usually embedded within green space (see Meiji Jingu in the heart of Tokyo as an example), however with the industrialisation and development of large cities, more and more shrines are found dwarfed by concrete and steel. Sometimes you may even find a torii inside a shopping mall!

You’ll soon approach the ‘honden’, or the inner sanctuary of the shrine. This is where you’ll be able to donate money and make a prayer or wish. However, before you do this you must purify yourself at what is called the ‘temizuya’. You grab a small wooden ladle in your right hand, scoop some water and pour it over your left. Switching hands, you then pour the water over your right hand. Again you pour water into your left hand and bring it up to your mouth. You don’t need to drink it but it signifies that you are purifying yourself nonetheless. Lastly you pour water again over your left hand and raise the ladle up so the remaining water cleans the ladle. It sounds confusing, but once learned you never forget!

After purification, you can approach the honden and make a donation. Most people donate 5 yen coins because of the luck associated with the word, in Japanese ‘goen’ can mean ‘5 yen’, but also ‘fate’ or ‘relationship’. You throw the coin into the donation box, or ‘saisenbako’, and then ring a bell that overhangs the box. This alerts the kami to your presence. Now you are finally ready to make your wish. The traditional way to make a wish is to bow twice, clap your hands twice, keeping your hands together after the second clap, and then making your wish. After the wish is made, you bow once more and turn away from the honden.

Now you’ve done it! Your first ‘omairi’, or shrine visit. However, it does not end here. Once you’ve finished your visit, you can head over to the ‘juyosho’ and pick up some shrine goods and trinkets. Shrines offer a large selection of unique goods tailored to the shrine and the kami enshrined in the honden. One popular piece is known as an ‘ema’, or votive tablet. Usually adorned with patterns that

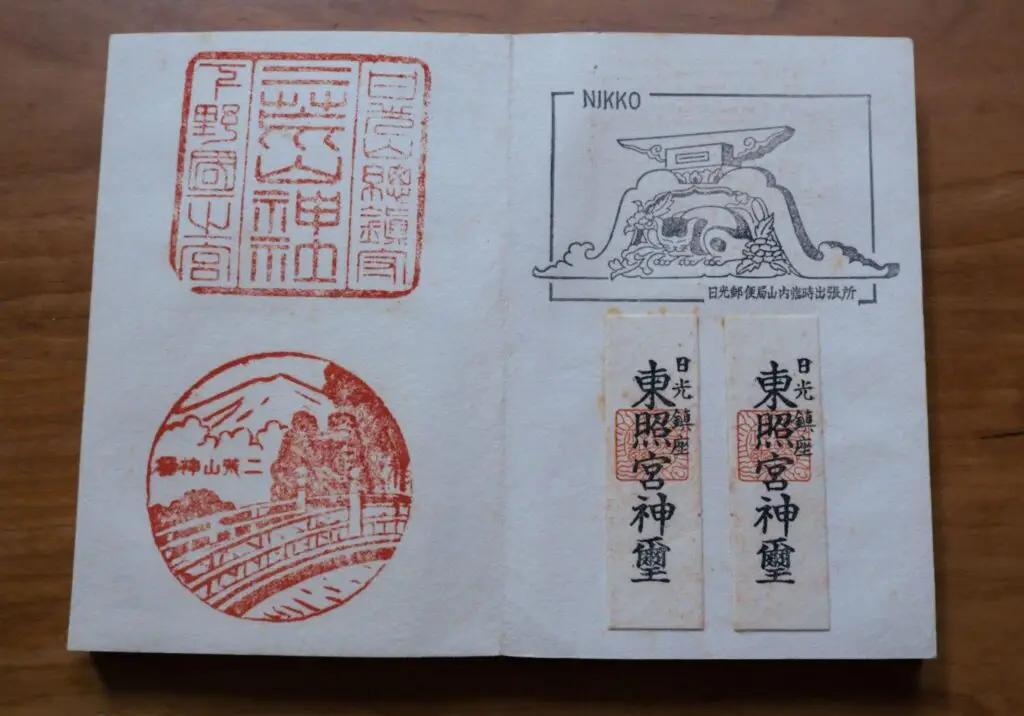

relate to the shrine, with an ema you write another wish on it and leave it hung up at a specific part of the shrine ground. People also take them home as souvenirs. Another popular good is called an ‘omamori’. These small bags contain written prayers for various causes, such as good luck, good health, passing exams, or even mountain climbing. Traditionally you keep the omamori on your person or backpack, ensuring that the good luck will stay with you. It is also common to return the omamori after a year to the shrine you got it from as the luck is supposed to run out after a year. Many shrines hold festivals during the new year, burning the old offerings as thanks for the protection that they gave during the previous year. However there is nothing wrong with keeping your omamori longer, especially as many tourists do not have the opportunity to come back after a year. Other potential goods you could get from a shrine include ‘ofuda’, a household amulet hung in one’s residence, ‘omikuji’, or fortunes, and ‘goshuin’, or shrine stamps. Written in what is called a ‘goshuinchō’, these stamps commemorate your visit, and have of late become a focus of collectors. As every goshuin is different depending on the shrine, many people have begun collecting as many as they can.

Shrines are complex, traditional institutions within Japan. However, contrary to how they may seem, shrines are also evolving alongside the modern Japanese city. If you look at any form of social media, you can find shrines have official accounts, advertising their products and festivals. Some are more active than others, with modern, sleek set-ups, while others still look quite dated, reminiscent of Japan’s still tenuous connection with digitalisation and modernisation.

While sorting through my grandmother’s Japanese antiques, I stumbled upon some old journals. In them she documented her travels throughout the country, from Nikko to Nara, from Nasu to Hiroshima. Along the way she collected various stamps from the many shrines and locales she visited. Coincidentally, some of the shrines she visited are ones that I was able to see in person when I studied in Tokyo. Namely Itsukushima Shrine in Hiroshima, one of the most famous shrines in Japan, alongside Meiji Jingu, Ise Jingu, and Izumo Taisha. Of the shrines on her list, I’ve yet to travel to a substantial amount. Konpira-gū, Nikko Tōshogū, Tōdaiji of Nara, her footsteps remain untraced. I hope that in the future I will have the opportunity to follow in my grandparents footsteps, see the sights they saw, experience the Japan they often waxed on about.

When it comes to Japan, of all those that travel there, many tend to gravitate toward a specific niche of the country. Whether it’s anime, manga, anarchism, or economics, something from the country becomes a person’s favourite thing. For me, it was shrines. I sometimes wonder why, is it the peacefulness in the busy of the city, the uniqueness of their goods and architecture, their deep history, or maybe something distinctly intangible. I’ve yet to narrow an answer, but to find it I know but one thing – There’s a lot of shrines left to visit.

Owen Ishii graduated from the University of Oxford with an MSc in Japanese Studies. His research focused on the digitalisation of Shinto shrines and their usage of social media and the internet. He currently works in communications in London. In his off time you can find him hiking, taking photos, or on the golf course.

– All photos by the author